The Medium and the Message

Part 1: Where have all the soldiers gone?

As disastrous months in Britain’s history go, May 1941 must rank quite high up the list. If you're still under the impression that Dunkirk had been the nadir in the nation’s struggle for survival against the German war machine then you've been seriously misled; a victim of post-war national propaganda. In actual fact, the unbelievable incompetence shown by our political and military elite at the outset of the war in 1939 continued unrelentingly until the middle of 1942 and, arguably, way beyond that date. Having been ignominiously ejected from Norway, Belgium and France at the start of the war, the British Army was destined to suffer a whole series of further humiliating defeats culminating in the fall of Singapore in February 1942 and the final collapse of Tobruk in June the same year. And while the leaders of the nation demonstrated their ineptitude, it was left to the ordinary people to show fortitude because it was the latter that suffered the brunt of these calamities. And as calamities go, May 1941 contained some of the worst.

The month began in the shadow and shame of the fall of Greece to the Germans and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from the Greek mainland. The month would end with the evacuation of the same force from the island of Crete after a further failure of leadership, the loss of many of the navy’s precious ships and even claims of officers deserting their troops in their haste to save their own skins. In North Africa, British successes against the Italians had been reversed by the arrival of a German army and the loss of Egypt seemed a very acute possibility.

The month began in the shadow and shame of the fall of Greece to the Germans and the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from the Greek mainland. The month would end with the evacuation of the same force from the island of Crete after a further failure of leadership, the loss of many of the navy’s precious ships and even claims of officers deserting their troops in their haste to save their own skins. In North Africa, British successes against the Italians had been reversed by the arrival of a German army and the loss of Egypt seemed a very acute possibility.

May also saw the blitz that had devastated London, Coventry and Plymouth extend its tentacles to Liverpool, Belfast, Glasgow and many other British cities. Essential food supplies bound for British ports from across the world were threatened by heavy shipping losses to U-boat attacks in the Atlantic and the British people faced the prospect of being starved into surrender.

Things were so bad that, on the 10th May, Rudolf Hess, the deputy leader of the Third Reich, parachuted into Scotland in order to meet with the leaders of the peace movement and conclude a treaty which would leave the Germans free to focus all their energy on the invasion of the Soviet Union. Unluckily for him (and those lords and ladies who were plotting the overthrow of the coalition government) he landed in the wrong place and was arrested by some ordinary squaddies from the Home Guard who were unaware that several members of the aristocracy had planned a warm welcome for him.

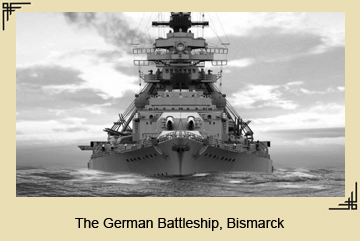

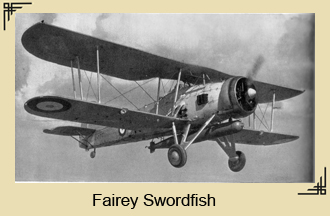

The future looked very bleak. Fortunately, something happened that would drop a little welcome light into this pit of despair. On May 27th the Royal Navy, which had been primarily occupied in plucking the British Army out of the water up until now, hunted down and sank the prize German battleship, Bismarck, as it raced for  safety to the port of Brest on the west coast of France. This wasn’t a victory without cost. In the process of stopping the raider from breaking out into the Atlantic and ravaging our merchant shipping, HMS Hood, the pride of the Royal Navy, had been sunk along with almost all of its fifteen hundred crew members. And it wasn’t only the navy’s one hundred ships pursuing the Bismarck that finally brought the enemy to book. Besides the invaluable intelligence provided by the code-breakers, it was a neutral American pilot flying out from the Irish Republic in his Catalina who had re-established contact with the Bismarck, and the crucial damage to the Bismarck’s rudder which made her incapable of steering to safety had been delivered by a flight of antiquated Swordfish biplanes from the Fleet Air Arm.

safety to the port of Brest on the west coast of France. This wasn’t a victory without cost. In the process of stopping the raider from breaking out into the Atlantic and ravaging our merchant shipping, HMS Hood, the pride of the Royal Navy, had been sunk along with almost all of its fifteen hundred crew members. And it wasn’t only the navy’s one hundred ships pursuing the Bismarck that finally brought the enemy to book. Besides the invaluable intelligence provided by the code-breakers, it was a neutral American pilot flying out from the Irish Republic in his Catalina who had re-established contact with the Bismarck, and the crucial damage to the Bismarck’s rudder which made her incapable of steering to safety had been delivered by a flight of antiquated Swordfish biplanes from the Fleet Air Arm.

But that didn’t alter the fact that Britain had delivered a decisive blow against the growing belief in German invincibility. It was a cause for celebration. You can get a taste of just how much this meant to the people involved in co-ordinating the chase for the raider in Edith Pargeter’s novel ‘She Goes To War’. Edith, who later became a famous author writing under the name of Ellis Peters, was a Wren at the time, serving in the Western Approaches Command Centre, a massive underground bunker complex set deep beneath the streets of Liverpool, built to coordinate naval operations in the North Atlantic. And Edith was on duty there during the hunt for the Bismarck. In her novel, published just one year after the event, she conveys the excitement and commitment of all those who took part. It was an especially poignant moment because she, like the rest of the population of Liverpool, Birkenhead and Bootle, had just endured the horrific May Blitz that had left the city and its docks in ruins.

But that didn’t alter the fact that Britain had delivered a decisive blow against the growing belief in German invincibility. It was a cause for celebration. You can get a taste of just how much this meant to the people involved in co-ordinating the chase for the raider in Edith Pargeter’s novel ‘She Goes To War’. Edith, who later became a famous author writing under the name of Ellis Peters, was a Wren at the time, serving in the Western Approaches Command Centre, a massive underground bunker complex set deep beneath the streets of Liverpool, built to coordinate naval operations in the North Atlantic. And Edith was on duty there during the hunt for the Bismarck. In her novel, published just one year after the event, she conveys the excitement and commitment of all those who took part. It was an especially poignant moment because she, like the rest of the population of Liverpool, Birkenhead and Bootle, had just endured the horrific May Blitz that had left the city and its docks in ruins.

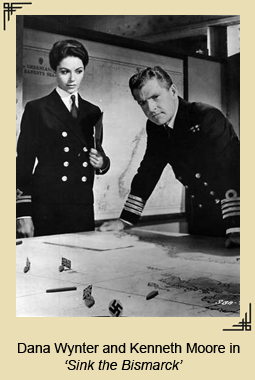

So much of a morale-booster was the sinking of the Bismarck, cloaking the thick catalogue of disasters, that it entered into the psyche of the British people and, in 1960, they made a movie out of the event. Starring Kenneth Moore,our most prestigious stiff-upper-lip, upper-middle-class character-actor as its hero, Sink the Bismarck relates all the twists and turns involved in the pursuit, the despair and elation of the people and the narrowness of final victory. And, In order to add a little spice to the story, Kenneth Moore was provided with a doting female companion in the shape of Dana Wynter, an extremely beautiful and curvaceous Wren officer who turns out to be just the type of self-sacrificing woman every stoic British hero should be issued with.

So much of a morale-booster was the sinking of the Bismarck, cloaking the thick catalogue of disasters, that it entered into the psyche of the British people and, in 1960, they made a movie out of the event. Starring Kenneth Moore,our most prestigious stiff-upper-lip, upper-middle-class character-actor as its hero, Sink the Bismarck relates all the twists and turns involved in the pursuit, the despair and elation of the people and the narrowness of final victory. And, In order to add a little spice to the story, Kenneth Moore was provided with a doting female companion in the shape of Dana Wynter, an extremely beautiful and curvaceous Wren officer who turns out to be just the type of self-sacrificing woman every stoic British hero should be issued with.

After the six day ordeal toiling deep beneath the ground, plotting and planning, our exhausted hero and heroine emerge together, triumphant, from the depths of the bunker into the glorious spring morning sunlight; into the streets of…… London?

After the six day ordeal toiling deep beneath the ground, plotting and planning, our exhausted hero and heroine emerge together, triumphant, from the depths of the bunker into the glorious spring morning sunlight; into the streets of…… London?

I’m not sure if Edith Pargeter and all those other naval personnel who served at that time in the Western Approaches ever minded that their efforts in the epic story had been transported in the telling to our capital city. Anyway, what difference does it make?

You only need to look back over the century prior to the making of this movie to see why it does matter. During that time the population of this country had increased massively on the back - or under the heel – of the Industrial Revolution, depending on which side of the class divide you were from. That population was engaged in a whole range of diverse industries and in services supporting those industries. There were woollen mills, cotton mills, steel manufacture, shipbuilding, chemical production and heavy and light engineering of all kinds. There were the canal and railway networks providing transport for these industries as well as the largest merchant marine in the world importing the raw materials and exporting the finished goods. And, of course there were the mines providing the coal that powered it all. Massive numbers of people employed all over the nation, from Aberdeen down to Southampton, from Hull across to Cardiff. These people were as diverse as the industries in which they served and as proud of their idiosyncrasies as they were of their skillsets.

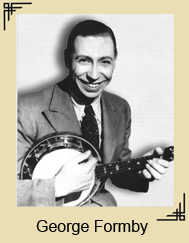

This diversity has only rarely been reflected in our national culture. Whether we are talking about the music and drama we prize as high art, the literature we preserve over time or the movies that we  produce, predominantly, this has been a culture of the middle to upper class. So, while in the 1930’s, the BBC, would find no problem in broadcasting a play by Shakespeare, packed with innuendo and sometimes outright lewd humour, it did not hesitate to ban from broadcast the songs of George Formby, possibly the most popular British comic entertainer of his time. Popularity to the BBC is relative. Popular with which class is the defining question. And don’t think that things have changed. In this cultural myopia, London together with the Home Counties is the nation and middle class tastes and preoccupations, no matter how they transmute over the decades, are the definition of nationality.

produce, predominantly, this has been a culture of the middle to upper class. So, while in the 1930’s, the BBC, would find no problem in broadcasting a play by Shakespeare, packed with innuendo and sometimes outright lewd humour, it did not hesitate to ban from broadcast the songs of George Formby, possibly the most popular British comic entertainer of his time. Popularity to the BBC is relative. Popular with which class is the defining question. And don’t think that things have changed. In this cultural myopia, London together with the Home Counties is the nation and middle class tastes and preoccupations, no matter how they transmute over the decades, are the definition of nationality.

Any wonder then that in the movie, Sink the Bismarck we see a command centre manned almost entirely by senior officers, ships crewed almost entirely by senior officers. This is the story of how we were led, not by donkeys but by lions, and victory belongs to them – defeat is somebody else’s fault. The only time we hear from any ordinary seamen in the course of the movie it comes in the form of light relief as they mutter and moan or demonstrate their indiscipline. Unlike Edith Pargeter and the majority of the other Wrens involved in the real hunt of the Bismarck, Dana Wynter is not an ordinary rating but a Second Officer! Well, we can’t have the ruling class mixing with the lower orders, can we? And, since this is a story about members of the British establishment then, obviously, it should be set in London, where the British establishment hang out, at least when the bombing stops.

This is not to say that the movie wasn’t produced, directed and acted with great professional competency. The ability of the narrative to deal with such a complex set of events in a comprehensible way owes a great deal to the book on which it was based. Hunting the Bismarck (also published as Last Nine Days of the Bismarck) and later changed to Sink the Bismarck to cash in on the movie’s popularity was written by C. S. Forester, author of the Hornblower novels amongst other major works. The novel is little more than a hundred pages long. In fact, it’s hardly accurate to describe it as a novel. The telling of this historical event comes to us at a remarkable pace, down phone-lines, in radio broadcasts, through semaphore signals, along telegraph cables, by newspaper headlines. It has a cinematic quality to it –a ‘quick-edit’ composition of news-reel shots intermingled with re-enacted dramatic sequences. The orders of the officers predominate in the soundscape, yes, but we also hear the shouts of the dockyard workers loading the supplies, and the voices of the ordinary sailors struggling to keep warm in the freezing, stormy waters of the North Atlantic, resting between watches, setting torpedoes, aiming the guns, dying:

In the bombed out streets of Portsmouth an elderly mother was walking with her shopping bag. She stopped when she saw the newspaper seller beginning to write up a headline on his contents bill.

“H-O-O-D” he began and then went on “S-U-N-K”. The woman stood staring and horrified for some seconds, the tears beginning to run down her cheeks. She turned away, bowed with sorrow. [page 52]

All of these ordinary voices are drowned out in the movie by the whimperings of our two romantically attached leading characters.

I suppose the special effects team deserve mention for their skill in adapting and improving methods available to them at the time to enact convincing sea battles with model ships. The model Swordfish aircraft were not so convincing though and now appear embarrassingly inadequate. Overall, though a noteable achievement, matching British talent with American finance. Yes, American money is a big player in British cinematic history as we shall see. Twentieth Century Fox was the financier in this case and Dana Wynter, though an English actress, was plying her trade in America at the time and under contract to them.

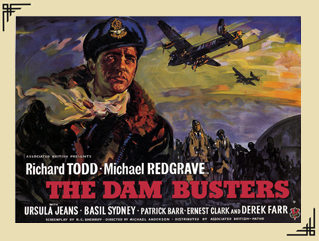

May 1941 had more than its fair share of disasters but, post-war and deep into the Cold War, it was best to forget about them and celebrate the victories. So we ignore the ragged and inept reality of how our leadership actually performed and instead create the myth of the heroic officer class. Sink the Bismarck was typical of the War Movie genre that Britain was producing at the time. Similar stories included The Dam Busters, The Cruel Sea and Reach for the Sky. The Battle of the River Plate, made in 1956, is almost a blueprint for Sink the Bismarck though with better production values as you would expect coming from the Powell and Pressburger stable, and it used real ships too! Here we see the captains of the British cruisers, charging at the dastardly enemy like medieval knights on their steeds with just one or two lowly squires in attendance.

May 1941 had more than its fair share of disasters but, post-war and deep into the Cold War, it was best to forget about them and celebrate the victories. So we ignore the ragged and inept reality of how our leadership actually performed and instead create the myth of the heroic officer class. Sink the Bismarck was typical of the War Movie genre that Britain was producing at the time. Similar stories included The Dam Busters, The Cruel Sea and Reach for the Sky. The Battle of the River Plate, made in 1956, is almost a blueprint for Sink the Bismarck though with better production values as you would expect coming from the Powell and Pressburger stable, and it used real ships too! Here we see the captains of the British cruisers, charging at the dastardly enemy like medieval knights on their steeds with just one or two lowly squires in attendance.

There even developed a sub-genre of Prisoner-of-war escape stories which demonstrate the indefatigable spirit of the officer class as they plan and execute their daring escapes, though they fail to explain how they were prisoners in the first place. In these tales of heroism, the ordinary soldier, sailor or airman is only ever a cipher, moaning and mumbling in the background, played by the extras.

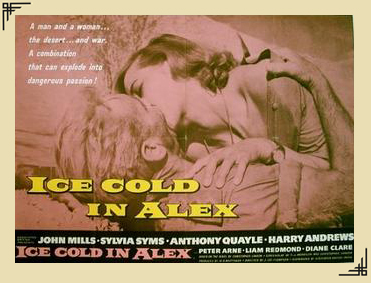

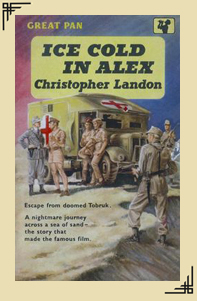

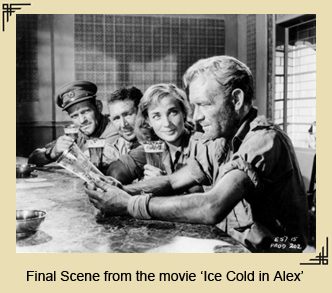

Even the excellent Ice Cold in Alex, possibly the best war movie produced in those post-war decades, sells its soul in its screen realisation. Made in 1958 and directed by J. Lee Thompson, the movie owes more than a smidgen of its success to the fact that it remains so true to the original novel, written by Christopher Landon, with its depiction of camaraderie in the face of adversity, its clear characterisation, clever plot, and its pacey dialogue. But it diverges from the book in one crucial and revealing way: the love-interest in the story is transferred from the beautiful nurse and the handsome sergeant-major to an affair between the nurse and the captain. Again, what does it matter? You could argue that it tightens up the screenplay by focusing our attention on one main character, Captain George Anson, a man on the verge of nervous collapse, acted brilliantly by John Mills. And you could hardly see Harry Andrewes, who plays the sergeant-major, as a romantic lead. But the latter is a matter of casting.

Even the excellent Ice Cold in Alex, possibly the best war movie produced in those post-war decades, sells its soul in its screen realisation. Made in 1958 and directed by J. Lee Thompson, the movie owes more than a smidgen of its success to the fact that it remains so true to the original novel, written by Christopher Landon, with its depiction of camaraderie in the face of adversity, its clear characterisation, clever plot, and its pacey dialogue. But it diverges from the book in one crucial and revealing way: the love-interest in the story is transferred from the beautiful nurse and the handsome sergeant-major to an affair between the nurse and the captain. Again, what does it matter? You could argue that it tightens up the screenplay by focusing our attention on one main character, Captain George Anson, a man on the verge of nervous collapse, acted brilliantly by John Mills. And you could hardly see Harry Andrewes, who plays the sergeant-major, as a romantic lead. But the latter is a matter of casting.

Read the book and you find that this love-interest between Sister Diana Murdoch and sergeant-major Tom Pugh is important because it is challenging British military conventions; it is breaking a taboo about rank and class. This theme is just as significant in the book as the fraternisation that occurs between the German spy, Otto Lutz and captain Anson at the end of the story with the ‘all against the desert’ motif – something that would still have been received somewhat ambivalently by a British audience in 1958. Sister Diana Murdoch, played by the luscious Sylvia Syms, has ‘two pips’ and so is officer class and she is conscious of the fact that her love for Tom will be seen as problematic. Tom is also aware and is initially reserved and always respectful to her because of her rank until she makes it clear to him that she doesn’t care about those things and that their love transcends such mores.

Read the book and you find that this love-interest between Sister Diana Murdoch and sergeant-major Tom Pugh is important because it is challenging British military conventions; it is breaking a taboo about rank and class. This theme is just as significant in the book as the fraternisation that occurs between the German spy, Otto Lutz and captain Anson at the end of the story with the ‘all against the desert’ motif – something that would still have been received somewhat ambivalently by a British audience in 1958. Sister Diana Murdoch, played by the luscious Sylvia Syms, has ‘two pips’ and so is officer class and she is conscious of the fact that her love for Tom will be seen as problematic. Tom is also aware and is initially reserved and always respectful to her because of her rank until she makes it clear to him that she doesn’t care about those things and that their love transcends such mores.

The movie, on the other hand, reinforces the class divide by switching the affair from Tom to Captain Anson. So something that is central to the novel is corrupted in its cinematic retelling. Unlike the movie which concludes with Anthony Quinn, who plays Otto Lutz, riding into captivity with his military police escort, the novel continues just a little beyond this point with captain Anson wishing Tom and Diana good luck with their marriage and telling them that he wants to give the bride away. Then, with symbolic nod to the social revolution that the war had precipitated, the final paragraph describes the two lovers holding hands outside the bar in Alexandria, being eyed by a redcap who is preparing to come over and check them for being improperly dressed and for holding hands. Tom goes to slip his hand loose but Diana stops him, saying:

The movie, on the other hand, reinforces the class divide by switching the affair from Tom to Captain Anson. So something that is central to the novel is corrupted in its cinematic retelling. Unlike the movie which concludes with Anthony Quinn, who plays Otto Lutz, riding into captivity with his military police escort, the novel continues just a little beyond this point with captain Anson wishing Tom and Diana good luck with their marriage and telling them that he wants to give the bride away. Then, with symbolic nod to the social revolution that the war had precipitated, the final paragraph describes the two lovers holding hands outside the bar in Alexandria, being eyed by a redcap who is preparing to come over and check them for being improperly dressed and for holding hands. Tom goes to slip his hand loose but Diana stops him, saying:

“Don’t let go darling. Everything – is going to be all right – for all of us.”

Unfortunately, this message is considered inappropriate by the time we reach the reactionary late fifties.

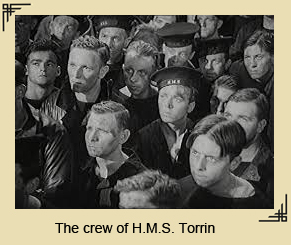

So Sink the Bismarck was a child of its time. Compare this then with a movie actually produced during the war: In Which We Serve. Set in the same month as the hunt for the Bismarck, this movie tells the tale of an ordinary ship’s crew before and during the battle for Crete. Not quite ‘ordinary’ actually. The destroyer portrayed in the story, H.M.S. Torrin, is a thinly disguised H.M.S. Kelly, which had been captained by non-other than Lord Louis Mountbatten, a prominent member of the Royal Family, former playboy, later to be the instigator of the disastrous Dieppe raid before becoming Viceroy of India and preciding over the deaths of millions of people when he decided to hasten the partition of the country. He was even accused of involvement in a plot to overthrow the elected government in the 1960’s and was killed when the I.R.A. placed a bomb on his pleasure boat in the 1970’s. Nevertheless, In Which We Serve provides an intriguing contrast to Sink The Bismarck.

So Sink the Bismarck was a child of its time. Compare this then with a movie actually produced during the war: In Which We Serve. Set in the same month as the hunt for the Bismarck, this movie tells the tale of an ordinary ship’s crew before and during the battle for Crete. Not quite ‘ordinary’ actually. The destroyer portrayed in the story, H.M.S. Torrin, is a thinly disguised H.M.S. Kelly, which had been captained by non-other than Lord Louis Mountbatten, a prominent member of the Royal Family, former playboy, later to be the instigator of the disastrous Dieppe raid before becoming Viceroy of India and preciding over the deaths of millions of people when he decided to hasten the partition of the country. He was even accused of involvement in a plot to overthrow the elected government in the 1960’s and was killed when the I.R.A. placed a bomb on his pleasure boat in the 1970’s. Nevertheless, In Which We Serve provides an intriguing contrast to Sink The Bismarck.

Written, produced, partly directed and starring Noel Coward as the de rigueur steadfast captain of the ship, the film actually begins with a fascinating montage showing the construction of the ship, the skills of the tradesmen and the sweat of the labourers involved. We then jump forward to see the ship in battle, intercepting enemy transports on their way to Crete. In this sequence, all members of the crew are involved in the fighting. The ship is then sunk by enemy aircraft (another embarrassingly poor special effects sequence) with some of the survivors managing to swim to a dingy. From this point we are presented with a sequence of flash-backs providing an insight into the personal lives of selected members of the crew, from the ordinary rating played by John Mills, the non-commissioned Petty Officer played by Bernard Miles, to the captain himself, played by Coward. We aren’t far away from traditional stereotypes in any of these characters but we are reminded that the war involved the efforts of the whole nation and not just the ruling class. As John Mills says while listening to Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlin on the radio complaining that the outbreak of war had come as a bitter personal blow:

Written, produced, partly directed and starring Noel Coward as the de rigueur steadfast captain of the ship, the film actually begins with a fascinating montage showing the construction of the ship, the skills of the tradesmen and the sweat of the labourers involved. We then jump forward to see the ship in battle, intercepting enemy transports on their way to Crete. In this sequence, all members of the crew are involved in the fighting. The ship is then sunk by enemy aircraft (another embarrassingly poor special effects sequence) with some of the survivors managing to swim to a dingy. From this point we are presented with a sequence of flash-backs providing an insight into the personal lives of selected members of the crew, from the ordinary rating played by John Mills, the non-commissioned Petty Officer played by Bernard Miles, to the captain himself, played by Coward. We aren’t far away from traditional stereotypes in any of these characters but we are reminded that the war involved the efforts of the whole nation and not just the ruling class. As John Mills says while listening to Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlin on the radio complaining that the outbreak of war had come as a bitter personal blow:

“Well, it ain’t exactly a bank-holiday for us!”

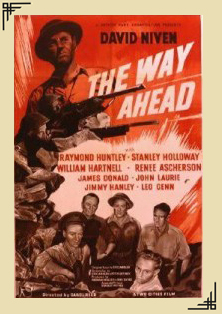

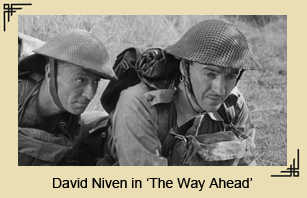

The movie struck a chord with the public and, despite Coward’s rather camp performance in attempting to capture the aristocratic characteristics of his friend, Louis Mountbatten, it is still interesting to watch today. The same can’t be said for The Way Ahead, a movie produced a few years later that tried to do the same for the army that In Which We Serve did for the navy. Despite the assembly of quite an impressive production team (written by Eric Ambler and Peter Ustinov, directed by Carol Reed, starring David Niven, William Hartnell, Stanley Holloway, Trevor Howard (uncredited), John Laurie and the youthful Jimmy Hanley) it creaks under the weight of the propaganda message it has to carry. Jimmy Hanley plays the part of Geoffrey Stainer, the cynical ‘ordinary man’ who resents the suspension of his liberty when he’s conscripted into the army where he imagines he will be bullied and persecuted into blind obedience. While he is vocal in his resentment he lacks the moral fibre to do anything about it other than complain to his mates who are nothing more than a discontented rabble at the beginning of the movie. James Donald playing Private Evans Lloyd, a

The movie struck a chord with the public and, despite Coward’s rather camp performance in attempting to capture the aristocratic characteristics of his friend, Louis Mountbatten, it is still interesting to watch today. The same can’t be said for The Way Ahead, a movie produced a few years later that tried to do the same for the army that In Which We Serve did for the navy. Despite the assembly of quite an impressive production team (written by Eric Ambler and Peter Ustinov, directed by Carol Reed, starring David Niven, William Hartnell, Stanley Holloway, Trevor Howard (uncredited), John Laurie and the youthful Jimmy Hanley) it creaks under the weight of the propaganda message it has to carry. Jimmy Hanley plays the part of Geoffrey Stainer, the cynical ‘ordinary man’ who resents the suspension of his liberty when he’s conscripted into the army where he imagines he will be bullied and persecuted into blind obedience. While he is vocal in his resentment he lacks the moral fibre to do anything about it other than complain to his mates who are nothing more than a discontented rabble at the beginning of the movie. James Donald playing Private Evans Lloyd, a  petty council official in civvy street, knows his civil rights and does use these rights to take his complaints to a higher level. As it turns out, the army is not the autocratic, inhuman body they had imagined but a humane and caring institution which always has the welfare of its members at heart. This compassionate aspect is epitomised in the character of David Niven playing Lieutenant Jim Perry. As a consequence of his benevolent leadership, the rabble is transformed into an effective fighting unit of the British Army. Embarrassing to watch now, it should be remembered that David Niven, who had made quite a reputation for himself in American movies by this time, was one of the few British movie-stars to return to this country when the war broke out. Others included Leslie Howard and Laurence Olivier. Most of the rest chose to remain in their safe haven along with some notable left-wing literary celebrities like the former outspoken critics of fascism, W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood.

petty council official in civvy street, knows his civil rights and does use these rights to take his complaints to a higher level. As it turns out, the army is not the autocratic, inhuman body they had imagined but a humane and caring institution which always has the welfare of its members at heart. This compassionate aspect is epitomised in the character of David Niven playing Lieutenant Jim Perry. As a consequence of his benevolent leadership, the rabble is transformed into an effective fighting unit of the British Army. Embarrassing to watch now, it should be remembered that David Niven, who had made quite a reputation for himself in American movies by this time, was one of the few British movie-stars to return to this country when the war broke out. Others included Leslie Howard and Laurence Olivier. Most of the rest chose to remain in their safe haven along with some notable left-wing literary celebrities like the former outspoken critics of fascism, W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood.

Although of little artistic merit, The Way Ahead does reveal by its very instigation the underlying attitude of the British public that, just as in the First World War, the professional army had completely failed to match up to the militarism of Germany, had mostly been destroyed in the process, and that it would be a conscripted citizen army that would have to take up the challenge.

The citizens in the British Merchant Navy were also playing their part and suffering heavy losses in the process. Once again, the British propaganda machine recognised the need to pay tribute to these men and just like In  Which We Serve, San Demetrio, London is a film that celebrates the efforts of the whole crew in the story of a merchant oil tanker, heavily damaged by the German raider, Admiral Sheer, on her voyage from Nova Scotia to the Clyde. With fires raging fore and aft and the tanker’s highly inflammable cargo about to explode at any minute, the crew abandon the San Demetrio and take to the lifeboats. Made in 1943 and directed by Charles Frend who had begun his career working as an editor on many of Alfred Hitchock’s British films of the 1930’s, San Demetrio, London is actually a dramatized version of a true story. Somehow the ship remains afloat and one of the lifeboats containing a handful of the original crew members find her drifting in the Atlantic. They re-board her, manage to put out the fires and, with just this skeleton crew and no charts, they restart the engines and bring her safely to her original destination on the Clyde.

Which We Serve, San Demetrio, London is a film that celebrates the efforts of the whole crew in the story of a merchant oil tanker, heavily damaged by the German raider, Admiral Sheer, on her voyage from Nova Scotia to the Clyde. With fires raging fore and aft and the tanker’s highly inflammable cargo about to explode at any minute, the crew abandon the San Demetrio and take to the lifeboats. Made in 1943 and directed by Charles Frend who had begun his career working as an editor on many of Alfred Hitchock’s British films of the 1930’s, San Demetrio, London is actually a dramatized version of a true story. Somehow the ship remains afloat and one of the lifeboats containing a handful of the original crew members find her drifting in the Atlantic. They re-board her, manage to put out the fires and, with just this skeleton crew and no charts, they restart the engines and bring her safely to her original destination on the Clyde.

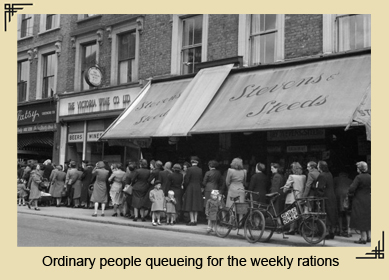

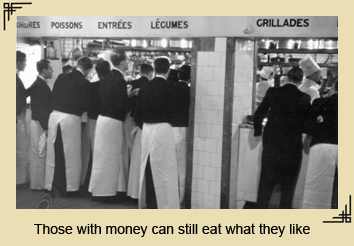

Whereas The Way Ahead is a clumsy propaganda exercise, San Demetrio, London slightly better, In Which We Serve has the saving grace of being an effective allegory of the nation - its population battered and beaten-about but resolute all the same. Yet, by 1960, allegory has been replaced by mythology. The war as depicted in British cinema is a glorification of the officer class. Victory replaces defeat. Hardly any mention in this medium any more of Norway, France, Greece, Crete,Tobruk, Singapore, Hong Kong, Burma or the Greek Islands. No place either for the 'other ranks'. We are taught to believe that the deliverance of the country was due to the heroism and sacrifice of those ‘few’ officer pilots  who flew their Spitfires and Hurricanes in the Battle of Britain and not the sacrifice of thousands of merchant sailors who suffered horrific deaths to keep the country fed in the much longer Battle of the Atlantic; men whose wages were stopped when their ship was sunk whether they survived the ordeal or not. Nor do we see the forbearance of the millions of people in cities like London, Liverpool, Belfast, Glasgow, Birmingham who suffered the months of bombing raids and came close to starvation on their diminishing rations while, of course, the elite still partied and feasted.

who flew their Spitfires and Hurricanes in the Battle of Britain and not the sacrifice of thousands of merchant sailors who suffered horrific deaths to keep the country fed in the much longer Battle of the Atlantic; men whose wages were stopped when their ship was sunk whether they survived the ordeal or not. Nor do we see the forbearance of the millions of people in cities like London, Liverpool, Belfast, Glasgow, Birmingham who suffered the months of bombing raids and came close to starvation on their diminishing rations while, of course, the elite still partied and feasted.

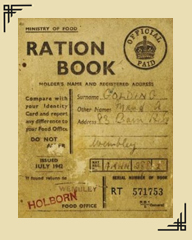

Oh yes! This isn’t part of the fictional retelling of the war but it was a very much a part of the real war. When rationing was introduced in 1939, it was presented as an egalitarian measure; something that would ensure ‘fair shares for all’. When shortages of essentials became acute, as government knew they would for an island nation that required 20 million tons of food imports alone each year to sustain its population, the authorities needed to ensure that commodity prices did not rise out of control: out of reach of the ordinary citizen on a minimum wage. But this was not altogether an altruistic measure. Prior to the outbreak of war the government statisticians had been hard at work and had calculated the exact minimum amount of food a person would need to continue to function and contribute to the war-effort. One lesson learnt from the experience of the First World War was that any future European conflict would be one of Total War involving all the population all of the time. A failure to ensure adequate food supplies to the working population would hamper this war effort and lead to civil unrest, perhaps even revolution. The spectre of the Russian Revolution still haunted the wealthy. So it was a pragmatic rather than an egalitarian measure.

Oh yes! This isn’t part of the fictional retelling of the war but it was a very much a part of the real war. When rationing was introduced in 1939, it was presented as an egalitarian measure; something that would ensure ‘fair shares for all’. When shortages of essentials became acute, as government knew they would for an island nation that required 20 million tons of food imports alone each year to sustain its population, the authorities needed to ensure that commodity prices did not rise out of control: out of reach of the ordinary citizen on a minimum wage. But this was not altogether an altruistic measure. Prior to the outbreak of war the government statisticians had been hard at work and had calculated the exact minimum amount of food a person would need to continue to function and contribute to the war-effort. One lesson learnt from the experience of the First World War was that any future European conflict would be one of Total War involving all the population all of the time. A failure to ensure adequate food supplies to the working population would hamper this war effort and lead to civil unrest, perhaps even revolution. The spectre of the Russian Revolution still haunted the wealthy. So it was a pragmatic rather than an egalitarian measure.

Along with rationing came the Black Market. Criminal gangs were able to exploit the shortages and establish an illegal market place with stolen goods which could be bought by those with enough money to pay. Shortages of manpower within the police-force and a fair amount of corruption made the job easy for gangland criminals like Billy Hill and Frankie Frazer who looked back on the war in their memoirs as their ‘happy time’. One famous case of ration fraud involved Ivor Novello, an immensely popular entertainer at the time; an actor, writer and composer; one of his most successful compositions was the First World War song, Keep the Home Fires Burning. As well as writing and appearing in musicals, he also starred in several movies. In 1944 he was convicted of using stolen petrol coupons which enabled him to exceed his ration allowance. He was sentenced to just four weeks in prison. An illustration of how the rich and famous considered themselves above such petty regulation. Novello was given a hero’s reception by his socialite friends when he returned to his show, The Dancing Years, after his release from prison. Almost forgotten now, it still inspired a song by the folk-singer, song-writer, Ewan McColl:

Along with rationing came the Black Market. Criminal gangs were able to exploit the shortages and establish an illegal market place with stolen goods which could be bought by those with enough money to pay. Shortages of manpower within the police-force and a fair amount of corruption made the job easy for gangland criminals like Billy Hill and Frankie Frazer who looked back on the war in their memoirs as their ‘happy time’. One famous case of ration fraud involved Ivor Novello, an immensely popular entertainer at the time; an actor, writer and composer; one of his most successful compositions was the First World War song, Keep the Home Fires Burning. As well as writing and appearing in musicals, he also starred in several movies. In 1944 he was convicted of using stolen petrol coupons which enabled him to exceed his ration allowance. He was sentenced to just four weeks in prison. An illustration of how the rich and famous considered themselves above such petty regulation. Novello was given a hero’s reception by his socialite friends when he returned to his show, The Dancing Years, after his release from prison. Almost forgotten now, it still inspired a song by the folk-singer, song-writer, Ewan McColl:

Ivor [tune: The Girl I Left Behind Me]

Oh, me name is Mike, or Mick, if you like

And me second name is O'Reilly;

And I'm doing me best with a two-year stretch

On account of a judge named Smiley.

I know all the nobs of the flash-boys mobs,

I'm an old sky-rocket diver;

But these were mugs of Wormwood-Scrubbs,

Compared with a bloke named Ivor.

He'd a juicy smile and a slick profile

And hair like a Soho waiter.

This ancient boy was the pride and joy

Of the smart London the-ater.

This West-End star had a Rolls-Royce car,

And Jack Nowles was his driver

And the dames would sigh when this car flashed by

For they knew that it carried Ivor.

Now, Ivor saw that the worst of the war

Was the petrol-rationing system

So he said to Nowles, "We must keep the Rolls

And think of a plan to twist 'em."

This three-star hit, he was doing his bit

For the democratic nations,

So he fixed up a scheme with a gallery queen

To evade the regulations.

Well, it worked O.K. until one day

The cops asked him some questions.

And they yanked our sport, under police escort

To the London, Bow Street sessions.

His character there was stripped as bare

As the dame they called Godiva,

And the judge, with a nod, said, "A month in quod

Will help to chasten Ivor."

So...they've fixed up a cell like a posh hotel

For this scribe of Tony drama.

And he strolls through the grounds in a dressing gown

And a pair of silk pajamas.

He lives like a duke and he has his own cook,

And he don't eat skilly neither,

For the governor of this lousy stir

Has a soft spot for old Ivor.

So, if you're inclined to turn to crime,

Just listen to my song, son,

Just become a star with a Rolls-Royce car

And then you can't go wrong, son.

Who cares if a lag does a 10-years drag

If that lad ain't got a stiver,

For you surely know any mug with dough

Can do as well as Ivor.

With such a show of irreverence to the rich and famous, it’s no wonder that Ewan McColl was monitored by MI5! But that’s not the half of it. The illegal Black Market wasn’t the only recourse the wealthy had to opt out of the austerity that had been imposed on the rest of society. There were quite legal ways too. Restaurants were exempt from food rationing. This meant that those with enough money could continue to enjoy the high-life and the diaries and memoirs of many of the rich-set record the rollicking time they had. Edith Pargeter, in her book She Goes To War, often refers to the unfair way in which the main burden of the war was borne by the poor and in one letter, her heroine in the story writes:

With such a show of irreverence to the rich and famous, it’s no wonder that Ewan McColl was monitored by MI5! But that’s not the half of it. The illegal Black Market wasn’t the only recourse the wealthy had to opt out of the austerity that had been imposed on the rest of society. There were quite legal ways too. Restaurants were exempt from food rationing. This meant that those with enough money could continue to enjoy the high-life and the diaries and memoirs of many of the rich-set record the rollicking time they had. Edith Pargeter, in her book She Goes To War, often refers to the unfair way in which the main burden of the war was borne by the poor and in one letter, her heroine in the story writes:

“I know there are ways around food rationing,ways out of service, ways of being safe and amassing more money – if you have money enough”

She also records one very unsavoury incident which, I’m sure, is drawn from actual experience. Talking about an affluent but unnamed hotel in Liverpool, she recalls:

“We fed as if in peace-timeand danced to soft music; and I thought of the mobile canteens doling out soup to the bombed-out women down by the docks and I felt sick……

“We fed as if in peace-timeand danced to soft music; and I thought of the mobile canteens doling out soup to the bombed-out women down by the docks and I felt sick……

….the same hotel, one of our biggest and wealthiest, distinguished itself early one blitz-morning by refusing food to a bunch of wet, grimy smoke-blackened AFS men who had been fighting fires on the docks all night under heavy bombing.”

Still, Britain had never been an equal society; had never even pretended to be such. Unlike France, egalitarianism isn’t a word attached to our national identity. Britain had fought a series of ferocious wars against revolutionary France at the turn of the Nineteenth Century in order to stop radical ideas like these spreading to our shores. Two of our greatest national heroes, Horatio Nelson and the Duke of Wellington, had taken part in that struggle, the latter becoming Prime Minister in 1828 and vehemently opposing even limited democratic reform in the country.

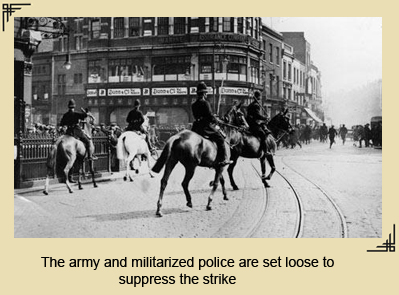

In 1819, a meeting was held in St Peter’s Field in Manchester attended by ordinary citizens of the city including many families. They had come to hear the the speech by Henry Hunt, who was proposing greater political representation for the population of Manchester; they had virtually none at the time. Without any provocation, the audience was charged by a troop of mounted militia, their swords swinging down on the unarmed crowd. These drunken, undisciplined militarised police killed sixteen people and seriously injured more than six hundred: men, women and children. It didn’t take long before commentators writing about the event to draw the comparison between this atrocity and the battle of Waterloo. We now know it as The Peterloo Massacre.

Meanwhile, the dissolute Royal Family in the persons of George IV and his queen Caroline weren’t afraid of parading their squalid affairs in public and living a life of contemptuous decadence. Such was the state of British society. Every tiny step forward in the path to the limited democracy we enjoy today was paid for with the lives of innocent people and not by the benevolence of those who rule over us as is often claimed. But now, in the hour of need…..well, perhaps we could forget about such inequalities and leave this other stuff behind us. ‘All in this together’ is a phrase that echoes down the years and usually means bad news for the poor.

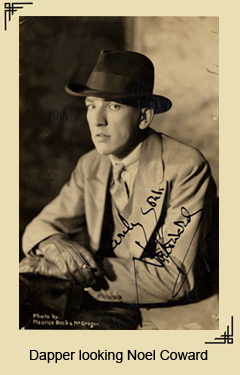

‘All in this together’ was the message behind the making of the movie This Happy Breed, produced in 1944. This was the second collaboration between David Lean and Noel Coward, only this time Lean became the sole director behind the project while the movie was based on a play written by Coward and also produced by him. Unlike many of his associates, Coward, who had thrown himself into the war effort with energy and spirit, was critical of Ivor Novello’s attitude:

"He's been fighting like a steer to keep going as before the war and hasn't done a thing for the general effort"

David Lean had established quite a reputation for himself between 1931 and 1942, working as a film editor in the British movie industry and Noel Coward had turned to him as a technical advisor when he began putting together a team to produce In Which We Serve. While Coward was the uber confident stage director, he knew he lacked the technical knowledge required for movie-making. During the production of the film, especially in scenes in which he wasn’t personally involved, Coward would leave the direction entirely to Lean. This Happy Breed was only Lean’s second movie as director and already we can see his potential as a conveyor of tales on an epic scale.

This Happy Breed tells the story of the Gibbons family from the end of the First World War up until 1939. Although epic in its span of historical events: the return of the warriors from the battlefields of France; the Depression; the General Strike; the death of a king; the abdication of another king; the Munich Crisis; the murmurings of another war, the story is actually a very close study of domestic relationships. In an accomplished opening edit, Lean presents us with a roof-top view of Clapham Common, London, panning across from the river, over the clustered terraced streets below and then down to number 17, Sycamore Road, the camera entering the house through an open first-floor back-window and tracking down the stairs to the front-door where it waits for the Gibbons family to make their entrance. More than a nod to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane here I think. The door opens and in come the family, taking possession of their newly rented house in which almost all of the action will take place.

This Happy Breed tells the story of the Gibbons family from the end of the First World War up until 1939. Although epic in its span of historical events: the return of the warriors from the battlefields of France; the Depression; the General Strike; the death of a king; the abdication of another king; the Munich Crisis; the murmurings of another war, the story is actually a very close study of domestic relationships. In an accomplished opening edit, Lean presents us with a roof-top view of Clapham Common, London, panning across from the river, over the clustered terraced streets below and then down to number 17, Sycamore Road, the camera entering the house through an open first-floor back-window and tracking down the stairs to the front-door where it waits for the Gibbons family to make their entrance. More than a nod to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane here I think. The door opens and in come the family, taking possession of their newly rented house in which almost all of the action will take place.

The trailer for the movie describes it as a story about ‘An ordinary London family’ and the Gibbons hover somewhere between upper working-class and lower middle-class. Frank Gibbons, the father, has a job working for a travel agent. Ethel Gibbon is a housewife. They have three teenage children, two daughters and a son: Vi, Queenie and Reg. They also have living with them Ethel’s mother, Mrs Flint, and Frank’s widowed sister, Sylvia. Yet, somehow or other, on Mr Gibbon’s single income (at least at the beginning of the story), they manage to support this extended family in a fairly comfortable manner and are still able to afford a home help. This apparent ambiguity in status is reflected in the attitudes of the family. At one point, Robert Newton, playing the part of Mr Gibbons complains:

“A few years ago we had Reg naggin’ at us because we were livin’ of the fat of the land while the poor workers were starvin’. Now we have Queenie turnin’ on us because we’re not grand enough for her.”

Frank Gibbons is a man of simple pleasures and conservative attitudes but with a liberal understanding of other people’s views. Helping to break the General Strike by working as a volunteer bus driver he nevertheless sympathises with his son, Reg, who had been demonstrating on the side of the strikers. While showing his paternalistic understanding of his son’s actions, he still manages to condemn socialism as something rather silly, something his son will grow out of as, indeed, he and his communist friend, Sam, eventually do, brought down to earth by the women they love.

Frank Gibbons is a man of simple pleasures and conservative attitudes but with a liberal understanding of other people’s views. Helping to break the General Strike by working as a volunteer bus driver he nevertheless sympathises with his son, Reg, who had been demonstrating on the side of the strikers. While showing his paternalistic understanding of his son’s actions, he still manages to condemn socialism as something rather silly, something his son will grow out of as, indeed, he and his communist friend, Sam, eventually do, brought down to earth by the women they love.

Frank Gibbons provides a sense of stability in a time of turbulent change, both historic and domestic. He has an instinctive appreciation of the realities of life and isn’t carried away on waves of popular emotion. Most of all, despite his station in life (whatever that is), he is patriotic. He is the reconciler within his family and, symbolically, within the nation. That, at least, is the character that Coward paints.

First written in 1939 as a wake-up call to the nation, the outbreak of the war meant that the project had to be postponed and the play wasn’t produced until 1942. By this time the movie came to be made in 1944, things had changed dramatically. Britain no longer stood alone; Russia and America were now in the war and Germany was on the defensive; an allied victory seemed inevitable. Now, due to the delay in production, the message of the film had the benefit of hindsight. Frank Gibbon had been proved right in his scepticism over appeasement. Amongst the citizen army, navy, and air-force, and the workforce of the nation as a whole, there was a sense of ‘pay-back time’. A distinct whiff of socialism was in the air. For Lean, a patrician by birth, and Coward, who had ‘risen from humble beginnings’, as they say, and who had ingratiated himself with the beau monde prior to the war, there were some misgivings over this, as is evident in Frank’s philosophic reflections on where socialism fails:

First written in 1939 as a wake-up call to the nation, the outbreak of the war meant that the project had to be postponed and the play wasn’t produced until 1942. By this time the movie came to be made in 1944, things had changed dramatically. Britain no longer stood alone; Russia and America were now in the war and Germany was on the defensive; an allied victory seemed inevitable. Now, due to the delay in production, the message of the film had the benefit of hindsight. Frank Gibbon had been proved right in his scepticism over appeasement. Amongst the citizen army, navy, and air-force, and the workforce of the nation as a whole, there was a sense of ‘pay-back time’. A distinct whiff of socialism was in the air. For Lean, a patrician by birth, and Coward, who had ‘risen from humble beginnings’, as they say, and who had ingratiated himself with the beau monde prior to the war, there were some misgivings over this, as is evident in Frank’s philosophic reflections on where socialism fails:

“Where we go wrong is trying to get things done too quickly. We don’t like things done too quickly in this country. It’s like gardening, we’re used to planting things and watching them grow. Think what a mess there’d be if all the flowers and vegetables came popping up all in a minute. That’s what all these social reformers are trying to do, trying to alter the way of things all at once.”

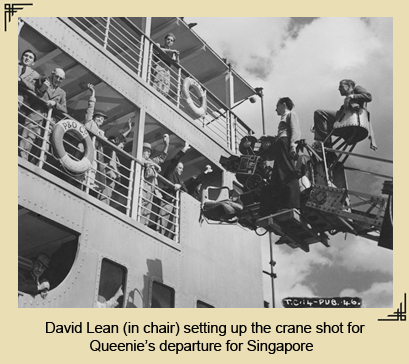

It’s this kind of political message that led actor Robert Donat to turn down the role of Frank Gibbons when Lean offered it to him. But despite their class bias and the none-too-subtle admonition against adopting left-wing views, Coward and Lean deliver a convincing story of a family living  through uncertain times and facing up to a fair share of tragedy in their lives: Frank’s sister, Sylvia, had been widowed by the First World War; Reg and his wife are killed in a car crash; daughter Queenie runs off with a married man, making her mother bitter with shame and resentment; and Frank’s mother-in-law, vocal throughout the first two acts, is absent from the finally scenes. Still they endure. And, despite appearances, this story doesn’t have a happy ending either. When Queenie returns to the fold, contrite and subdued and married to the devoted son of the next door neighbour, played by John Mills, it would seem that contentment has settled over Frank and Ethel’s lives as they look after their baby grandson and reflect on their upcoming retirement. But the same hindsight that enabled the audience to appreciate Frank’s perspicacity when denouncing appeasement, also enabled them to see that Queenie, leaving to join her husband in Singapore, was heading for disaster. Even though they wouldn’t have guessed at the treatment they would receive at the hands of their Japanese captors, they would, by 1944, know the fate of Singapore itself.

through uncertain times and facing up to a fair share of tragedy in their lives: Frank’s sister, Sylvia, had been widowed by the First World War; Reg and his wife are killed in a car crash; daughter Queenie runs off with a married man, making her mother bitter with shame and resentment; and Frank’s mother-in-law, vocal throughout the first two acts, is absent from the finally scenes. Still they endure. And, despite appearances, this story doesn’t have a happy ending either. When Queenie returns to the fold, contrite and subdued and married to the devoted son of the next door neighbour, played by John Mills, it would seem that contentment has settled over Frank and Ethel’s lives as they look after their baby grandson and reflect on their upcoming retirement. But the same hindsight that enabled the audience to appreciate Frank’s perspicacity when denouncing appeasement, also enabled them to see that Queenie, leaving to join her husband in Singapore, was heading for disaster. Even though they wouldn’t have guessed at the treatment they would receive at the hands of their Japanese captors, they would, by 1944, know the fate of Singapore itself.

The passage of time has swept the board clean of all ambiguity. Winston Churchill, our war-time Prime Minister, is now regarded as a sort of demi-god. Quite a transformation from the ruthless opportunist who repeatedly swapped political parties in order to gain office, stood opposed to the independence of Ireland and India, proposed using poison gas against  Arabs and Kurds during the Iraqi rebellion of 1920 because they needed to be reduced to submission as economically as possible, felt that it was right for racially superior people like himself to dominate and even eliminate aboriginal peoples, sent a brace of gunboats to the Mersey to put down a strike in 1911, instigated the disastrous Dardanelles campaign in the First World War, threw the country into financial meltdown by returning us to the gold standard in 1925 and saw the Fascism of Mussolini and Franco as a good thing and at one time thought Hitler the saviour of his people. Not quite the man whose image Boris Johnson would like to assume today. And his conduct of the war does not bear too much scrutiny either. It was lucky for us that Hitler decided to invade Russia and, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, to declare war on America.

Arabs and Kurds during the Iraqi rebellion of 1920 because they needed to be reduced to submission as economically as possible, felt that it was right for racially superior people like himself to dominate and even eliminate aboriginal peoples, sent a brace of gunboats to the Mersey to put down a strike in 1911, instigated the disastrous Dardanelles campaign in the First World War, threw the country into financial meltdown by returning us to the gold standard in 1925 and saw the Fascism of Mussolini and Franco as a good thing and at one time thought Hitler the saviour of his people. Not quite the man whose image Boris Johnson would like to assume today. And his conduct of the war does not bear too much scrutiny either. It was lucky for us that Hitler decided to invade Russia and, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, to declare war on America.

Only recently, Martin Bell, one-time reporter and protector of our moral well-being as the politician known as ‘the man in the white suit’, referred to the ‘revisionist historians’ who only appeared after the publication of Alan Brookes’ diaries in 1957. Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff during the Second World War, chief military advisor to the Prime Minister, was highly critical of Churchill and his erratic decision-making. His entry for 10 September includes this passage:

".....And the wonderful thing is that 3/4 of the population of the world imagine that Churchill is one of the Strategists of History, a second Marlborough, and the other 1/4 have no idea what a public menace he is and has been throughout this war ! It is far better that the world should never know, and never suspect the feet of clay of this otherwise superhuman being. Without him England was lost for a certainty, with him England has been on the verge of disaster time and again."

You can regard this as revisionism if you like, but you have to totally ignore the contemporary evidence if you do. Churchill was a class warrior, hated and despised in the industrial centres of the nation and, even during the war, never had the popular support of the nation no matter how much foreign peoples might admire him. So it comes as no surprise that he was thrown out of office on the immediate return to peace. We don’t hear much of this in the deferential accounts of his career these days.

The nation which had risen against the incompetence of its rulers in the first general election after the war still had to face the consequences of its fight for survival; the devastation of its cities, the bankruptcy of its economy, and a prolonged period of austerity for its population. While in the cinema, the story of the war was revised with the gradual exclusion of the ordinary citizen f rom the account, the people that had endured the actual war continued to endure. Radical reform was underway that would eventually transform education, health, housing and social welfare but these could not alleviate the privations being suffered by the population of a country in hopeless debt yet still trying to hold on to a disintegrating empire and resume its role as a great power. But the world had changed. Russia was now our enemy and (half of) Germany our friend. George Orwell captured the mechanics of this psychological somersault perfectly in his book 1984 which had originally been entitled 1948 – not a book about the distant future but of our ever-present capacity to accept political redirection and obliterate the recent past from our memories. So, vanquished from the cinematic account of the war, demobbed from their service to the screen, where did all the ordinary soldiers, sailors, Wrens and women factory workers go during this period of unequal deprivation?

rom the account, the people that had endured the actual war continued to endure. Radical reform was underway that would eventually transform education, health, housing and social welfare but these could not alleviate the privations being suffered by the population of a country in hopeless debt yet still trying to hold on to a disintegrating empire and resume its role as a great power. But the world had changed. Russia was now our enemy and (half of) Germany our friend. George Orwell captured the mechanics of this psychological somersault perfectly in his book 1984 which had originally been entitled 1948 – not a book about the distant future but of our ever-present capacity to accept political redirection and obliterate the recent past from our memories. So, vanquished from the cinematic account of the war, demobbed from their service to the screen, where did all the ordinary soldiers, sailors, Wrens and women factory workers go during this period of unequal deprivation?

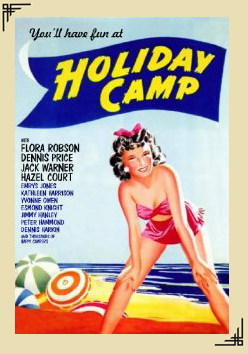

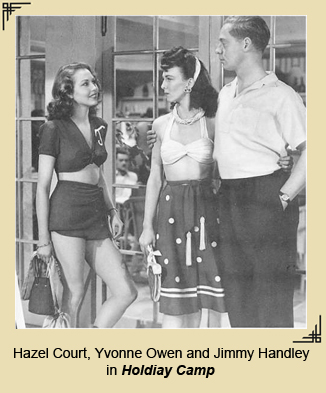

Where they had always been prior to the war; they went back to their traditional roles in the comedies and crime movies. Where else!  No surprise then that a slightly stockier Jimmy Hanley than we’d seen being moulded into an effective fighting soldier in The Way Ahead should appear in an immediate post-war comedy movie, still serving His Majesty but this time in the guise of a sailor in the Royal Navy, on leave on the east coast of England where he was supposed to meet up with his girl-friend. The movie was entitled Holiday Camp (1947) and it explores a new social phenomenon by a new director fresh from learning his trade making short documentary films to support the war effort. In a screenplay suggested by Godfrey Winn and written by Muriel and Sidney Box (its Producer) along with Ted Willis and Peter Rogers, Ken Annakin directs this compendium of inter-related stories about ordinary people enjoying their summer break in the Fairleigh Holiday Camp, which was not a very serious attempt to disguised the fact that it was based on and partly shot in the Butlin’s Holiday Camp at Filey.

No surprise then that a slightly stockier Jimmy Hanley than we’d seen being moulded into an effective fighting soldier in The Way Ahead should appear in an immediate post-war comedy movie, still serving His Majesty but this time in the guise of a sailor in the Royal Navy, on leave on the east coast of England where he was supposed to meet up with his girl-friend. The movie was entitled Holiday Camp (1947) and it explores a new social phenomenon by a new director fresh from learning his trade making short documentary films to support the war effort. In a screenplay suggested by Godfrey Winn and written by Muriel and Sidney Box (its Producer) along with Ted Willis and Peter Rogers, Ken Annakin directs this compendium of inter-related stories about ordinary people enjoying their summer break in the Fairleigh Holiday Camp, which was not a very serious attempt to disguised the fact that it was based on and partly shot in the Butlin’s Holiday Camp at Filey.

Holiday camps had first appeared in Britain prior to the First World War but had really taken off in the late 1930’s. They were large leisure sites for the masses where people were crowded together into villages of small chalets and offered continuous entertainment at the dance-halls, swimming pools, sports fields and fairgrounds. Everything you could possibly want on a holiday in one location. Everybody was cajoled into joining in with the fun through loud-speaker announcements and by the ever-attendant Red Coats. Families with children were provided with lots of facilities for the kids including child-minders. As one of the cast says while looking out on the huge crowd below, skipping around in ranks and singing communal songs:

“Do you see what I see? One of the strangest sights of the Twentieth Century; the great mass of people, all fighting for the one thing you can’t get by fighting for it: happiness.”

He comes to see that, in this ‘frantic search for pleasure’ the crowd is actually made up of individuals:

“each one of them tired and dispirited, eager for peace and yet frightened to be alone.”

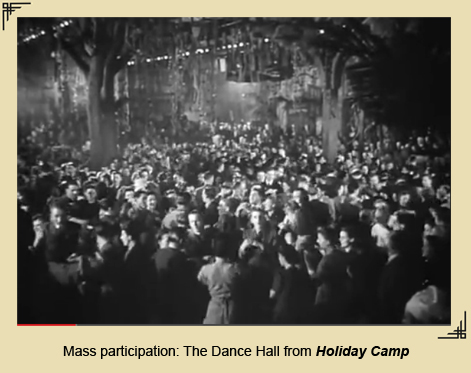

Annakin broke new ground by filming a considerable number of establishing and supporting shots for the movie on  location using his documentary skills while the actors performed their parts in studio sets constructed from the footage and stills that Annakin and his team brought back. Dozens of extras are used to surround the action in the studio and help provide that sense of mass participation that the camps encouraged. All the same the transition between the location and the studio sets isn’t totally seamless and you have to remember that this was a low budget movie.

location using his documentary skills while the actors performed their parts in studio sets constructed from the footage and stills that Annakin and his team brought back. Dozens of extras are used to surround the action in the studio and help provide that sense of mass participation that the camps encouraged. All the same the transition between the location and the studio sets isn’t totally seamless and you have to remember that this was a low budget movie.

The plots too, are pretty weak and the coincidences that bind them together are very contrived, based mostly on the need to share chalet accommodation with strangers. Even though these were strangers of the same sex, the movie can be quite risqué for its time – or should that be for how we regard that time today. They weren’t as innocent and demure as we’re sometimes led to believe – remember George Formby’s Little Stick of Blackpool Rock? There were many more, lesser known songs which played with sexual innuendo. One of these, recorded by Florence Desmond, a popular actress, comedienne and impersonator, is unashamedly about prostitution during the blitz and revels in double-entendre:

The deepest shelter in town

Don't run away mister

Oh, stay and play mister

Don't worry if you hear the sirens go

Though I'm not a lady of the highest virtue

I wouldn't dream of letting anything hurt you

And so before you go, I think you ought to know

I've got a cosy flat, there's a place for your hat

I wear a pink chiffon négligé gown

And do I know my stuff, but if that's not enough

I've got the deepest shelter in town.

I've got a room for two, a radio that's new,

An alarm clock that won't let you down,

And I've got central heat, but to make it complete,

I've got the deepest shelter in town.

Every modern comfort I can just guarantee

If you hear the siren call then it's probably me

And, sweetie, to revert, I'll keep you on the alert

I won't even be wearing a frown

So you can hang around here until the all clear

In the deepest shelter in town.

Now honey, I don't sing of an Anderson thing

Climbing in one you look like a clown

But if you came here to see, why Sir John would agree

I've got the deepest shelter in town.

Now Mr. Morrison says he's getting things done,

And he's a man of the greatest renown,

But before it gets wrecked, I hope you'll come and inspect

The deepest shelter in town.

Now I was one of the first to clear my attic of junk,

But when it comes to shelters nowadays it's all bunk.

So honey, don't get scared, it's there to be shared

And you'll feel like a king with a crown

So please don't be mean, better men than you have been

In the deepest shelter,

The neatest shelter,

The deepest shelter in town.

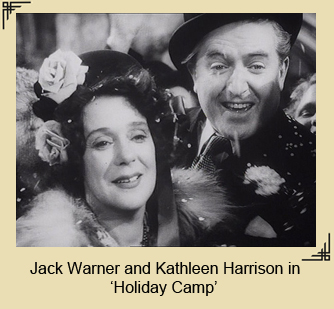

In between the comic misunderstandings and the clumsy romance scenes, Holiday Camp does provide an interesting insight into the social attitudes  and conditions of the working class in the immediate post-war era. The Huggett family are the main focus of the movie, with Jack Warner playing the part of Joe Huggett, a father of two and a recent grandfather of one while Kathleen Harrison plays Mrs Huggett, the harassed but coping grandmother. Their daughter, Joan, played by Hazel Court, is a young mother, widowed by the war and now on the lookout for a new husband and a suitable father for her child. In amongst the other campers there is an unmarried couple who have contrived to meet up at the camp only to discover that they are about to become parents with no visible means of support.

and conditions of the working class in the immediate post-war era. The Huggett family are the main focus of the movie, with Jack Warner playing the part of Joe Huggett, a father of two and a recent grandfather of one while Kathleen Harrison plays Mrs Huggett, the harassed but coping grandmother. Their daughter, Joan, played by Hazel Court, is a young mother, widowed by the war and now on the lookout for a new husband and a suitable father for her child. In amongst the other campers there is an unmarried couple who have contrived to meet up at the camp only to discover that they are about to become parents with no visible means of support.

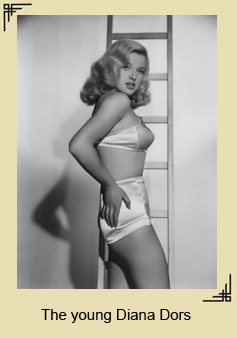

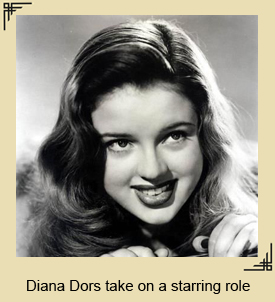

Using a very delicate touch, the screenplay does choose to handle these very real human issues here. The two sub-plots  are not the only indications that, yes, sex did exist back in the nineteen-forties; there are many hints at such sexual liaisons in the movie and we also see that Mr Hugget himself is an overt voyeur of the young nubile women of at the camp, viewing them constantly through his binoculars. Among those he has his eyes on is the fifteen year old Diana Dors (uncredited in this movie), an emerging sex-siren in the mould of Marilyn Monroe. No suggestion then that Joe’s behaviour was in any way abnormal or inappropriate at his age. No censure for those male members of the audience at a beauty contest practically salivating at the sight of the young women clad only in swimming costumes.

are not the only indications that, yes, sex did exist back in the nineteen-forties; there are many hints at such sexual liaisons in the movie and we also see that Mr Hugget himself is an overt voyeur of the young nubile women of at the camp, viewing them constantly through his binoculars. Among those he has his eyes on is the fifteen year old Diana Dors (uncredited in this movie), an emerging sex-siren in the mould of Marilyn Monroe. No suggestion then that Joe’s behaviour was in any way abnormal or inappropriate at his age. No censure for those male members of the audience at a beauty contest practically salivating at the sight of the young women clad only in swimming costumes.

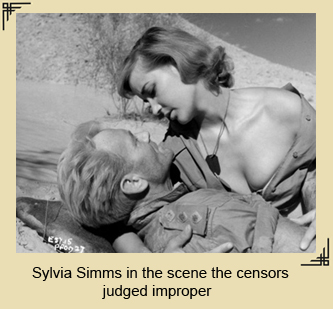

And the consequence of sexual activity, much more so then than now, is children! Unwanted, or more accurately, unsupportable children have been  a fact of life forever though it was probably during the Victorian era that attitudes to sexual profligacy and illegitimacy became so abhorrent to public sensibilities. This superimposed morality managed to conceal the hypocrisy of the ruling classes who exploited their position and privilege and celebrated their sexual indulgences in their memoirs. Meanwhile, sanctimonous bodies controlled all aspects of public life including the cinema. Strict censorship ensured that the ordinary public were never exposed to any overly 'lascivious' material. Innuendo is one thing, but flesh another. One victim of the censor's scissors was a scene from Ice Cold in Alex, where Syliva Syms was judged to have shown too much cleavage as she pressed herself down onto John Mills. It had to be re-shot.

a fact of life forever though it was probably during the Victorian era that attitudes to sexual profligacy and illegitimacy became so abhorrent to public sensibilities. This superimposed morality managed to conceal the hypocrisy of the ruling classes who exploited their position and privilege and celebrated their sexual indulgences in their memoirs. Meanwhile, sanctimonous bodies controlled all aspects of public life including the cinema. Strict censorship ensured that the ordinary public were never exposed to any overly 'lascivious' material. Innuendo is one thing, but flesh another. One victim of the censor's scissors was a scene from Ice Cold in Alex, where Syliva Syms was judged to have shown too much cleavage as she pressed herself down onto John Mills. It had to be re-shot.

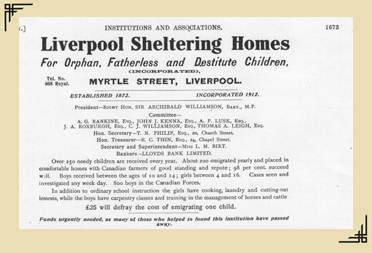

Still, the sanctimony of the time did not prevent young, unmarried couples from following their natural inclinations. They mated! They did it then as they’ve always done it. Often this led to pregnancy. In order to avert the moral  condemnation of the day, many such adventures led to illegal abortions or early marriages, some to the concealed adoption by close members of the mother’s family, others to the surrender of the children to ‘homes’. And, it just so happened, the charities that ran these homes had another service they could impart to the state. While such children were surplus to requirements here, the empire was crying out for young, white people to help 'tame the wilds'. In a scheme called Home Children, introduced by Annie MacPherson, a Scottish evangelical Quaker way back in 1869 and lasting right up until the 1970’s, hundreds of thousands of British children were dispatched to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Out of sight, out of mind, the pretence of Victorian decorum could continue.

condemnation of the day, many such adventures led to illegal abortions or early marriages, some to the concealed adoption by close members of the mother’s family, others to the surrender of the children to ‘homes’. And, it just so happened, the charities that ran these homes had another service they could impart to the state. While such children were surplus to requirements here, the empire was crying out for young, white people to help 'tame the wilds'. In a scheme called Home Children, introduced by Annie MacPherson, a Scottish evangelical Quaker way back in 1869 and lasting right up until the 1970’s, hundreds of thousands of British children were dispatched to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. Out of sight, out of mind, the pretence of Victorian decorum could continue.

So, the fate of children born outside of marriage could be grim and it was important that the situation with the young couple in Holiday Camp, once raised, should be resolved. And, of course it is. A well-to-do middle-class  lady, played by Flora Robson, provides the charitable solution. The widowed daughter of the Huggets, Hazel Court, finds her man in the form of the jilted Jimmy Hanley. The Huggets’ son, Harry, played by Peter Hammond, who has become entangled in a card-school and has been fleeced in it, is rescued by his street-wise father, Joe, who proves more than a match for the card-sharps, one of whom was played by John Blythe, who had played Reg in This Happy Breed. All nice and neat and mixed in with dollops of sentimentality and humour. But one sub-plot does jar. On the advice of Muriel Box, a murder plot was included in the script with a serial-killer in amongst the holiday-makers, seeking out his latest female victim. Played by Dennis Price, the 'lady-killer' entices a number of women into his web and eventually murders one of them. This sub-plot doesn’t fit comfortably with the other more mundane tales in this movie and nearly caused Billy Butlin, who complained about the inclusion of a murderer in one of his camps, to block the release.