Educational Technology: The Revolution has been postponed....again.

If, by some off-chance, you were to google the phrase 'Educational Technolgies' you might just find, in amongst all the hyperbole about a revolution in teaching and learning; references to e-Learning, i-Learning, m-learning; evangelistic exaltations for teachers to embrace the latest gaming gadget to emerge in the entertainment sector; funding opportunities for projects which demonstrate the potential of technology in the classroom – yes, in amongst all of this you might just find the odd sour note of illuminating disillusionment; the suggestion that, bluntly stated, the revolution in pedagogy which was promised has been postponed indefinitely. You WILL find it if you look. Unfortunately, repeatedly, the people who should be looking, just aren't.

Some years ago, in 2010, I attended a professorial lecture delivered by Professor Patrick Carmichael in the Art and Design Academy of the Liverpool John Moores University, the theme of which was the imminent demise of the 'lecture' as a player in the dissemination of knowledge and guidance to students . I was there because I was interested – I had a professional interest in the subject since I've been involved in education technology in one form or another for over twenty years now. As the presentation began, I felt a cold shiver run down my back. It was cold place. It was a very large, open kind of space; neutral and impersonal. It was a brand spanking new lecture theatre. Yes, a lecture theatre. The irony of delivering a lecture in a still-being-paid-for, tiered-seating lecture theatre on the death of the lecture had, apparently, escaped the eminent professor as I'm guessing it escaped most of those being lectured to. But it wasn't the room or the irony that made me squirm in my seat, or even the profs rather dry Powerpoint-backed delivery style. It was the thought that……..this is where I came in.

Some years ago, in 2010, I attended a professorial lecture delivered by Professor Patrick Carmichael in the Art and Design Academy of the Liverpool John Moores University, the theme of which was the imminent demise of the 'lecture' as a player in the dissemination of knowledge and guidance to students . I was there because I was interested – I had a professional interest in the subject since I've been involved in education technology in one form or another for over twenty years now. As the presentation began, I felt a cold shiver run down my back. It was cold place. It was a very large, open kind of space; neutral and impersonal. It was a brand spanking new lecture theatre. Yes, a lecture theatre. The irony of delivering a lecture in a still-being-paid-for, tiered-seating lecture theatre on the death of the lecture had, apparently, escaped the eminent professor as I'm guessing it escaped most of those being lectured to. But it wasn't the room or the irony that made me squirm in my seat, or even the profs rather dry Powerpoint-backed delivery style. It was the thought that……..this is where I came in.

Yes, these were the very same sentiments, entreaties and prophecies that I heard when I first started working at the LJMU in 1990. Back in those days, educational technology was still in the Age of Video. Slide carousels, overhead projectors, video-recorders and even audio cassettes were still the most prominent forms of technical  support that lecturers could deploy. Computers were beginning to appear in small clusters in remote locations. This was their incubation phase and within only a few years they had multiplied and had assumed their present ubiquitous status thanks to the impressive efforts of our computer department. Nowadays, students, lecturers and administrators alike all use the technology to reseach, prepare, communicate, organise and even plagiarise. There's no doubt that computer technology has had an enormous impact on all sector of our lives. Yes, we all use Powerpoint now. But that's not what the prof was talking about. And that's not what all those other ardent visionaries are talking about either. Their agitprop is directed at a revolution in pedagogy. A crusade against educational luddites; a jihad on current learning and teaching methodologies.

support that lecturers could deploy. Computers were beginning to appear in small clusters in remote locations. This was their incubation phase and within only a few years they had multiplied and had assumed their present ubiquitous status thanks to the impressive efforts of our computer department. Nowadays, students, lecturers and administrators alike all use the technology to reseach, prepare, communicate, organise and even plagiarise. There's no doubt that computer technology has had an enormous impact on all sector of our lives. Yes, we all use Powerpoint now. But that's not what the prof was talking about. And that's not what all those other ardent visionaries are talking about either. Their agitprop is directed at a revolution in pedagogy. A crusade against educational luddites; a jihad on current learning and teaching methodologies.

But, haven't we been here before?

As wave after wave of them go lunging into no-man's land only to find themselves tangled up on the wire, you begin to hear the cries of despair and disillusionment. Andras Szucs (2009), recounts how, a decade ago, ICTs were expected to transform higher education, making it more inclusive and flexible but that now, 'it seems the expectations about the revolution were somewhat exaggerated, linked to ambitious early e-learning visions'.

In an opening address to the 'Harnessing Technology: Building on Success' conference on 2nd December 2009, Stephen Crowne announced that the Government's vision is:

In an opening address to the 'Harnessing Technology: Building on Success' conference on 2nd December 2009, Stephen Crowne announced that the Government's vision is:

"for every learner, school, college and skills provider to be able to use technology effectively, intelligently and discriminatingly to support more effective learning, engage better with the wider community and support a thriving economy."

In his assessment of progress to date, he produces the statistics for the uptake of technology in schools and colleges and asks, 'Is this good enough?' His answer is NO!

"There are many examples throughout the education and skills sectors of successful adoption and deployment of technology. But technology is not yet fully embedded in a way that has transformed our basic processes or the dominant operating and delivery models."

You can even call that eminent educationalist, Rupert Murdoch, to the stand as a witness. In a speech to the eG8 conference in 2011 he took a deeply critical view of the educational establishment. His speech was reported in the Guardian newspaper:

You can even call that eminent educationalist, Rupert Murdoch, to the stand as a witness. In a speech to the eG8 conference in 2011 he took a deeply critical view of the educational establishment. His speech was reported in the Guardian newspaper:

"In every other part of life, someone who woke up after a 50-year nap would not recognize the world around him," Mr. Murdoch said, "But not in education. Our schools remain the last holdout from the digital revolution."

"A teacher waking up from a 50-year nap would find a classroom looks almost exactly the same as it did in the Victorian era. My friends, what we have here is a colossal failure of imagination and an abdication of our responsibilities to our children and grandchildren."

Well, there you go, who would dare argue with Rupert? Seriously though, this sense of anger and disappointment at the underachievement is not a new phenomenon but appears to be a constant, recurring theme. Step back through time and you'll get my point.

In an overview of the experiences, trends and tensions encountered in the development of eLearning policy in a number of countries, M. Brown et al.(2007) point to the new Action Programme in the Field of Lifelong Learning 2007-2013 (which includes the Erasmus programme for higher education) as evidence of the very limited impact of earlier initiatives by the European Union in this field.

In 2004, a policy paper from the European Open and Distance Learning (ODL) Liaison Committee looked back to 2000 when a European eLearning initiative had been launched to help equip its citizens with the skills necessary to participate in the new Information Society and to compete in the Knowledge Economy and concluded that the co-ordination and momentum behind this major initiative had largely disappeared. It sought to reinvigorate and realign the policy to make it more effective. But in 2006, the same body reports back on problems with their 2004 agenda and, though they are dealing here with 'life-long learning' in general rather than specifically with higher education, they again seek to address the deficiencies that are impeding the progress of eLearning.

Betty Collis and Marijk van der Wende (2002) in an American report for the Center for Higher Education Policy (cheps) compared the state of Technology and Change in Higher Education in an international survey. This draws attention to the gap between the vision and the reality. Higher Education institutions, they conclude, do not expect ICTs to lead to a revolution but rather adopt a 'business as usual' attitude and, while there is some stretching of the mould with regards to new technologies, the report questions whether this is adequate.

An editorial in the International Journal for Academic Development in 2001 by Christopher Knapper, called 'The Challenge of Education Technology' he looks forward to the dramatic transformation that developments in ICTs will have on teaching and learning higher education, "The potential is considerable and the claims for technology ambitious: that learning will be more active and interactive, more flexible, and will allow simulation of experiences that have been previously inaccessible". But he then reflects back on similar, unfulfilled promises made by earlier technologies.

I've rarely heard the argument put more succinctly than by Stephen Ehrmann, 'Technology and Revolution in Education: Ending the Cycle of Failure' in 2000.

"If these failures keep occurring, why has no one noticed? The first reason is "Moore's Amnesia:" each time computers become cheaper and more usable, they attract droves of new users who weren't around for the last cycle of error. They don't realize that they're about to make the same mistakes as their predecessors. Because of the influx of new funders, advocates and users (and the departure of those who were too badly burned the last time around), the field loses most of its memory of all the previous generations of disappointment."

Yes, but that was back in 2000 and here we are moving cautiously into 2013 and still the 'Rapture of the technology' continues. Take an even longer jump back in time. Jonathan Darby(1995) in a Times Higher Education article reflects on the situation way back then:

"Anyone who has been observing the educational technology scene for any length of time cannot fail to be struck by the many false dawns there have been. Language laboratories in the 1960s were one such - a useful tool for aspects of language learning but not the complete revolution in language teaching methods they were claimed to be."

And, despite a rising crescendo of expectation about ICTs, he feels a "wariness, a nagging feeling that we have been here before". Indeed we have and did he but know that we were destined to go back again and again.

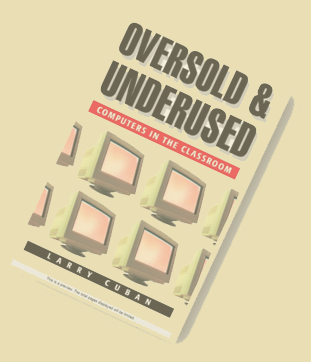

In a chapter entitled New Technologies in Old Universities, Larry Cubin explores the practice, expectation and the use of ICTs in high schools and universities in the USA. He begins by  recounting how the University of Stanford spent millions of dollars on a state-of-the-art audio-visual centre (Stanford Center) back in the 1970's, equipped with multiple large TV monitors, screens and projectors, simultaneous translation facilities and a form of 'student-responder', a hand-held keyboard allowing students to participate to some degree in the proceedings. He experienced this facility himself as a student, when the student-responders had already been disconnected and the centre was being used as a general purpose lecture theatre. When he returned in 1981 to teach, all the equipment except for the sound system had been removed. This anecdote serves as a forewarning for the new wave of expectation that Cubin experienced in 2001 when the claims being made for ICTs are similar to those that were made for film, radio and instructional television in the 1950's, 60's and 70's. And his own conclusion is that, despite the access that lecturers have to ICTs and their use of them in research, communication, administration, and preparation for teaching, that teaching practice had altered very little if atall as a result.

recounting how the University of Stanford spent millions of dollars on a state-of-the-art audio-visual centre (Stanford Center) back in the 1970's, equipped with multiple large TV monitors, screens and projectors, simultaneous translation facilities and a form of 'student-responder', a hand-held keyboard allowing students to participate to some degree in the proceedings. He experienced this facility himself as a student, when the student-responders had already been disconnected and the centre was being used as a general purpose lecture theatre. When he returned in 1981 to teach, all the equipment except for the sound system had been removed. This anecdote serves as a forewarning for the new wave of expectation that Cubin experienced in 2001 when the claims being made for ICTs are similar to those that were made for film, radio and instructional television in the 1950's, 60's and 70's. And his own conclusion is that, despite the access that lecturers have to ICTs and their use of them in research, communication, administration, and preparation for teaching, that teaching practice had altered very little if atall as a result.

And we don't have to stop there. We can go back even earlier. Reflecting on his career in 2007 in an article called 'A Long Look Back', Richard Hooper concludes that, while technology has found its niche in distance learning, the 'live teacher in the live classroom or lecture hall still remains the iconic centre he or she always was'. Get that Professor Carmicheal? Richard Hooper then goes on to describe how he had written an article 38 year previously in 1969 on the failure of educational technology (which was then video-based) despite the apparent abundance of funding. He quotes from his own article:

in an article called 'A Long Look Back', Richard Hooper concludes that, while technology has found its niche in distance learning, the 'live teacher in the live classroom or lecture hall still remains the iconic centre he or she always was'. Get that Professor Carmicheal? Richard Hooper then goes on to describe how he had written an article 38 year previously in 1969 on the failure of educational technology (which was then video-based) despite the apparent abundance of funding. He quotes from his own article:

"... educational technology ends up doing little else but perpetuating the traditional system of

education. It is an abiding irony of the newer media that despite their ability to revolutionize and

upgrade the quality of education they can by the same token prolong and mirror what is already

going on in school "

British Journal of Educational Technology Vol 39 No 2 2008 234

Despite these perennial false dawns, and disappointed expectations, the push to make more effective use of technology in the teaching room continues today, though with constantly revised approaches to make it more successful. In March 2009, HEFCE released a policy statement which "builds on the HEFCE strategy for e-Learning (HEFCE 2005/12) and focuses on enhancing learning, teaching and assessment through the use of technology" which provides guidance on how institutions can use technology to enhance learning, teaching and assessment.

Claudio Dondi (2009), while acknowledging that the last ten years was a phase of excessive enthusiasm (and "spectacularly excessive resistance"), he feels that there are now more reasonable expectations and attitudes towards ICTs and that it would be difficult to imagine learning taking place without 'the use of the technology, educational resources and social networks used by people in their everyday lives'.

The need to embrace technology-enhanced learning

So, what exactly are the key strategic drivers that make it so crucial that we embrace 'technology-enhanced learning' with much more ardour? The most prominent reason given is the changing economic model of the post-industrial nations (the Knowledge Economy) and the appearance of more aggressive international competition in the field of higher education. Mark Brown et al.(2007) express precisely this view:

"The economic rationale for investing in e-learning is particularly evident in Australia, Canada, United Kingdom and the European Union (and New Zealand) where the common goal is to create a competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy through the adoption of new digital technologies" In 2004 the European ODL Liaison Committee claims that ICT supported learning "is not an objective in itself but indispensible for bringing about the socio-economical changes in which the European Union has engaged itself".

The same committee goes further in 2006:

"It is widely accepted that Human Resources are the determining factor for the drive towards competitiveness and growth in the knowledge-based economy and are critical to the achievement of inclusiveness, social cohesion and equity. In parallel, globalisation, suggesting mobility for goods, services, labour, ideas and societal practices, coupled with the pervasive effect of the proliferation of information and communication technologies, is exercising a strong pressure on existing education and training (E&T) systems, which run the risk of losing relevance and effectiveness."

Dirk Schneckenberg (2009), referring to the same European-wide drive also draws attention to a new threat facing H.E. - Universities not only have to contend with competition from outside the Union, but also from corporate education providers, offering "commercial study courses in the higher education sector". It's this competition that is forcing universities to re-define their students as customers of educational services, adapt to new normative value systems, and also to transform themselves into entrepreneurial organisation, prepared for the competitive educational marketplace. And eLearning, he feels, is the key strategy in this transformation.

Andras Szucs (2009) also identifies the intensive challenges faced by the world of higher education due to the increase in competition brought about by globalisation.Even before the latest announcement of severe budget cuts facing H.E., Polly Curtis in the Guardian had forecast a deep financial crisis faced by universities in this country in November 2009; a combination of impending public spending and intense competition from abroad.

Andras Szucs (2009) also identifies the intensive challenges faced by the world of higher education due to the increase in competition brought about by globalisation.Even before the latest announcement of severe budget cuts facing H.E., Polly Curtis in the Guardian had forecast a deep financial crisis faced by universities in this country in November 2009; a combination of impending public spending and intense competition from abroad.

"Right across Europe we are seeing a new wave of education provision taught in English and indeed in Scandinavia too."

In 'How technology will shape learning: A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit' (2008), the authors point to the impact that technology has already had on higher education and the part it will play in the future:

"Nearly two-thirds (63%) of survey respondents from both the public and private sectors say that technological innovation will have a major influence on teaching methodologies over the next five years. In fact, technology will become a core differentiator in attracting students and corporate partners."

Some years earlier, in 'Implementing eLearning Programmes for Higher Education: A Review of the Literature', Kayte O'Neill et al. (2004), conclude that this international and corporate competition means that higher education institutions "cannot retain their traditional structure, in facilities and delivery via formal lectures and class based activity". This paper also draws attention to another driver in the need for H.E. to adapt to a more technology-supported learning-teaching model. This is the increase in student numbers and the 'diverse needs' of these students:

"Increasingly universities must provide quality and flexibility to meet the diverse needs of students – this will inevitably involve tailoring courses to suit differing educational needs and aspirations. Lecturers will be forced to fundamentally change their approach to teaching to accommodate the shift in student learning styles."

As well as the diverse needs of the students, HEFCE (2006) point out that the new economy is demanding higher skill-levels of its graduates: Institutions need to initiate more agile processes of curriculum design and delivery, and are discovering that technology can provide the efficiencies and flexibility they need.

Where did it all go wrong?

Having identified such a strong, pressing need, why has H.E. failed to adapt to wave after wave of new eLearning policy and directives as intended? One of the most common explanations given in the past for ignoring innovations was the 'not invented here syndrome' a term which is defined in Wikipedia as "the persistent social, corporate or institutional culture that avoids using or buying already existing products, research or knowledge because of its different origins". From my own experience I know of many local eLearning initiatives that were undertaken by lecturers or departments within this University and judged to have been 'successful', disseminated in reports or through Learning and Teaching conferences, but which were never followed-up even by other departments let alone other universities.

Back in 1995, Jonathan Darby stated:

"Some would argue that the "Not Invented Here Syndrome" is so strong in academia that any attempt to produce computer-based learning materials targeted at university courses is bound to fail."

The ODL committee concluded in 2006 that it is the lack of accumulated research findings behind the under utilization of innovative practice in mainstream teaching and learning, and that this leads both researchers and innovative practitioners to prefer to "start from scratch" rather than to build "on recent progress made by someone else".

Sometimes underfunding or the 'small- scaleness' of initiatives undertaken by enthusiastic lecturers is seen as the reason why successful practice fails to survive the early promise but, in a study of iCampus, a $25 million initiative funded by Microsoft at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) which ran from 1999-2006, and which funded several separate eLearning projects in the University, Stephen C. Ehrmann et al.(2006) provides an executive summary, outlining how these projects had improved learning at MIT by making it more authentic, collaborative, active and 'feedback-rich', but concludes:

"Nonetheless, wider adoption has been extremely difficult to promote, despite the fact that the materials are free and that over $2.5 million has been allocated for outreach. Because there is little incentive or support at most institutions to see out and adopt innovations from other institutions….

…Innovations rarely prosper for long at any one institution unless they also spread among many institutions; if wide use is achieved, the various users can support each other and long term survival of the innovation is far more likely. So widespread adoption for expensive R&D projects is a virtual necessity for getting full value for the original investment.."

The size of the budget and the money available for 'outreach' would certainly challenge any assumption that underfunding was the prime reason for the underachievement.

Another reason given for the dissatisfaction with progress is that the very structure of universities, and the decentralization of power within that structure, is inherently resistant to innovative methodologies. Dirk Schneckenberg (2009) feels the degree of autonomy that faculties have is one of the two main 'tensions' that exist within universities. These tensions contribute to the failure to achieve institutional-wide objectives in introducing technology-enhanced innovation since faculties do not have the competencies to respond to the challenges that ICT integration into the curriculum requires. Szucs (2009) also identifies the university structure as a barrier to progress:

"In higher education, institutional structures still tend not to allow managers and university directors to invest serious money and human resources in developments needed to achieve interactive self-paced material. Therefore, e-learning is often built into the tuition process, according to academic traditions. In the meantime, knowledge centre networking has been weaker than expected, and the expected virtualisation of universities did not really develop either." The Economist report (2008), 'How technology will shape learning', identify several things that might hinder technological innovation and suggest that "organisational practices may need adjustment to encourage faculty members to adopt new technologies".

The other contributing factors that might hinder progress, according to this report, are tenure and promotion policy. Jonathan Darby (1995), identified tenure as problematic:

"While a course syllabus may be set by the department or faculty, the way in which it is taught is normally left to the lecturers. This makes all courses highly personal and subject to revision whenever lecturing responsibility is passed on to someone else."

Dirk Schneckenberg (2009) sees the second 'tension' existing within universities that inhibits the adoption of technological innovation being the current reward structure which strongly favours the quality of research over the quality of teaching. Drawing his findings from the scientific community where research is "thoroughly assessed" while teaching is hardly assessed atall:

"As long as appointments to open positions as well as status and monetary rewards are mainly based on research portfolios of researchers, the marginalisation of teaching in the academic culture will continue. [quoting Scott and Gibbons, 2001]"

This leads inevitably, he feels, to an imbalance when it comes to career development and "the marginalisation of teaching in the academic culture" (p. 420). The consequent weak position of teaching expertise hinders any attempts by universities at an institutional level to introduce teaching innovation.

Other commentators feel that the lack of progress is simply a matter of out-right resistance by academic staff. Claudio Dondi (2009) for instance, sees that the last ten years have been a decade of excessive enthusiasm and "spectacularly excessive resistance". And in the 2004 policy paper from the European ODL liaison committee they state:

"Many encouraging developments have taken place also thanks to EU support, but those who were resisting eLearning from inside the education and training systems had the time to build their case against it, at least partly due to very low quality and simplistic promotional messages associated to first (and second) generations of eLearning provision."

This report even sees the term 'blended learning' as problematic since if offers the opportunity to those who wish to resist change to introduce small concessions to ICT based learning while continuing to deliver teaching in the same old manner.

In defense of those who are seen as resisting innovation, the European ODL Liaison Committee (2006 ) blame the manner in which innovation is introduced: "the ways to promote top-down innovation initiatives are not always 'user friendly', and the implementation models seldom allow people on the front-line – typically teachers and trainers – to take the necessary time and knowledge to become owners of the innovation proposed. That is usually stigmatised as "resistance to innovation" but is frequently a well-founded resistance to "unconvincing innovation", plans that do not match, nor negotiate with the visions of the world of the interested stakeholders. Institutional leadership should create top-down the necessary conditions for fruitful bottom-up initiatives." The persistence of traditional methods of teaching is highlighted by Andras Szucs in 2009:

"Nevertheless, recent analyses and system critics acknowledge that, at undergraduate level, ICT-supported solutions are largely supplementary to classroom teaching. ICT is primarily used to support existing teaching structures and traditional ways of tuition."

And the report from the Economist Intelligence Unit (2008) finds that, despite its benefits, technology is both disruptive and expensive and that faculty members may lack the motivation and the budget to invest in new methods of teaching.

In another paper, Claudio Dondi, (2005) summarizing a report from HECTIC (2002) lists many of these aspects and more as a reason the ineffectiveness of ICTs to change the status quo:

• Reward systems in higher education not aligned with promoting teaching or innovation

• Academic contracts which do not stimulate innovation

• Governance constraints of Universities

• Senior staff unfamiliarity with change management skills

• Cultural assumptions: traditional is best

• Loss of motivation of staff

• Inadequate physical infrastructures

• Lack of effective training and support for academic in eLearning development

Betty Collis and Marijk van der Wende (2002) describe in their analysis of research data a dichotomy between the perceptions of the decision-makers, at an institutional level and the teachers "on the front line". Those instructors who actually use the technology and are, in reality, "stretching the mould" in a gradual process, are less concerned about it, less impressed by it and have lower expectations of it than those at an institutional level who do not actually have to teach with it (page 35).

How Sound is the Case for eLearning?

One of the most interesting (disturbing) aspects of this prolonged preoccupation with pushing eLearning harder has been the underlying assumption that the argument is pedagogically sound. We are assured that eLearning is inclusive, provides flexibility and is adaptable to the diversity of the current student body; that it enables student-centred leaning, There is the impression that the pedagogical debate underpinning these claims has been held, is over, and no longer needs justification. Mark Brown et al. (2007) do challenge this stance:

"The value of e-learning is rarely questioned and the discourse is removed from any deeper consideration of educational policy. The missing question in the policy discourse is: What kind of education do we want e-learning to help deliver? "

Rarely questioned? It was once. Ehrmann et al. (2006) in their iCampus study mentions that early, favorable studies carried out in the 1970's and 80's by James Kulik that seemed to demonstrate that computer enhanced learning was more effective than traditional methods were later challenged by Richard Clark:

"Richard Clark then pointed out that self-paced instruction could also be implemented on paper, with similar instructional gains and argued that technology was merely a delivery vehicle with no impact on outcomes. Clark pointed to parallel research that had already documented the fact that if information was presented one way from expert to learner, the outcomes were on the average the same, no matter what technology was used to carry the transmission: a lecture hall, a book, a videotape, or any other technology of presentation. Clark concluded that what mattered was the learning activity, not the technology used to support it. "

However, this argument was subsequently dismissed. Perhaps it might be a good idea to re-examine it in the clearer light of hindsight?

Tara Brabazon (2007) in The University of Google, an impassioned and idiosyncratic defence of scholarship in changing times within H.E. challenges the motivation of those advocating technology enhanced-learning that delivers student-centred learning, flexibility and access:

"Although it is unpopular to admit, student centred-learning is an excuse for cheap learning. The 'convenience' to the student - which appeals to those who want an easy ride through their education - is cheating them of an academic, passionate confusing, challenging, complicated but precious learning encounter." (p. 77)

She points to the pressures on traditional institutions having to adapt to greater numbers of students and diverse learning and support needs:

"More students are attending our universities now than at any point in history. Courses and classrooms are overflowing. Resources are scarce, academic staff have less time to conduct professional development to render their teaching more efficient. Every new technological innovation – internet-mediated asynchronous communication, internet-mediated digital synchronous communication, i-lectures and podcasting – is seen to solve the 'problem' of lectures. " (p. 86-7)

This book isn't a condemnation of technology-enhanced learning but a critique of its misuse and the consequences of that misuse in leaving the very students who need more support to fend for themselves, without the experience or the discipline required for 'self-study':

"Access to education is different from flexible learning. The internet has become the bandage linking these two ideas. Actually, when students from non-traditional backgrounds attend university, they require more teaching, greater contact and more discussion of how information becomes knowledge. (p. 101)

..the increasing availability of information requires more discipline, more effort, more imagination, more commitment and more scaffolding from teachers and librarians. It is easy to place materials online. It is much harder to teach and learn how to manage, interpret and analyze digital text, sound and images. (p.77)

Flexible learning, with time-shifted materials available online, only increases the apathy and disconnection of students from their campus. ..... No technology – even a convergent one – intrinsically makes learning student-centred." (p.106)

Someone who is much more critical of the use of technology in education is Mark Bauerlein (Turned on. Plugged In, Online and Dumb: Student Failure Despite the Techno Revolution, October 21, 2008). Bauerlein chronicles a raft of studies which indicate that, far from being a beneficial influence, technology is having a detrimental effect on students' writing ability.

"Still, in spite of these underwhelming numbers, pro-tech advocacy continues. The disappointing results come years after the initial launch, and so people forget the promises put forward about how technology would transform learning. But with school budgets tight and student writing in critical condition, we need more accountability in the initiatives and more hard skepticism about learning benefits. And we need a lot less fervor for tools and screens that have only existed for a few years and whose human consequences are yet to be determined."

Is that it?

No, I could go on but I think I've made my point by now. And I hope that one day the Professor Carmichaels of the educational world will do their research first - there's a long history to this future thing!

I've been tempted to widen my argument and include something here about a related subject and my own particular bête noir, the 'educational games' syndrome. But that really needs a space of its own. So I'll take up the challenge in the second part of my polemic.